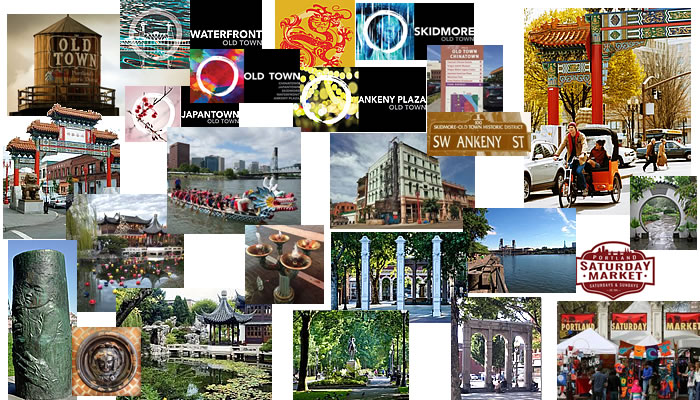

Here is a collage showing the different aspects of Old Town Chinatown

Old Town Chinatown Neighborhood is down in the middle of NW Portland, roughly bounded by Naito Parkway, Everett, 3rd, and Oak streets. It includes some of the Pearl, and all of the NW River area along the Willamette River. According to the neighborhood Association website, it includes, Old Town Waterfront, Skidmore, Japan Town, China Town, and Ankeny Plaza. It is mostly condos, some of the are built right along the river with breath taking views of the Willamette and the city beyond. There are walkways that go along the river that you can access from these condos, and even though you are right in the middle of the city, there are birds and wildlife that frequent the green spaces. You can even go over one of the bridges and get on the East Bank Esplanade, a floating bike-walking path, and then back over a bridge to the west side of the city. The river and it’s paths give you a breath of nature in the compact city environment. There are also a lot of restaurants, bars, and other businesses all around you, plus the Portland Streetcar, bus service, bike lanes, and easy walking!

Old Town Chinatown Neighborhood was known for it’s homeless population and high crime rate, plus alot of it was run down. It was also knows for its dance clubs, cocktail bars and Asian eateries. But in 2014, the Portland Development Commission’s voted in it’s 5 year Chinatown plan, which means putting at least $57 million from urban renewal funds to develop Old Town Chinatown Neighborhood. It has already started! And it seems like the area is getting as hot and popular as some of the other newer trendy areas, like Mississippi and Alberta! Being so close to the Pearl District, it is ripe for growth, and new business moving in, like the Pine Street Market, has brought up the area tremendously, and it looks like it will continue. This is something you don’t want to miss! Some of the best restaurants are in this building from Pollo Bravo (from the great Tasty N Sons owners), Marukin Ramen (one of just a few U.S. locations of the small Japanese chain), and finish up with an over-the-top sundae or dipped cone from Wiz Bang Bar, very similar to Salt & Straw. It is in the historic Carriage & Baggage Building and features nine of Portland’s best chefs and purveyors, in a casual, open layout.

Here are links to some of the condos in Chinatown

Parks and Museums in Old Town Chinatown Neighborhood

- The tranquil walled Lan Su Chinese Garden is state of the art, with native Chinese plants, and the Shanghai Tunnels underground passageways.

- The Japanese American Historical Plaza is a gorgeous setting on the waterfront. The flowering pink cherry trees line the river and make you feel like you may be in Japan. The large grassy area is perfect for relaxing on a nice day. The waterfront trail follows the river over the Steel Bridge and around on the Eastbank Esplanade, which is an urban park featuring a long floating walkway, plus a boat dock, walking & bike paths & public art, and then you can loop around over the Hawthorne bridge and back to the Tom McCall Waterfront Park. This is one of my favorite things to do!

- Portland Saturday Market is under the Burnside Bridge and has arts and crafts vendors, and urban boutiques and art galleries dot the area.

History of Old Town Chinatown Neighborhood

Chinese New year back in Old Portland

Chinese and Japanese History had some very sad moments in Portland. Here is the history of the Chinese people in early Portland, taken from the online webpage, museum of the city

The first Chinese immigrants arrived in Oregon territory in the 1850s. Portland’s Chinese immigrants shared many of the same issues found in other cities in the 1800s, social intolerance, racism, and restrictive laws made life hard.

Some Portlanders shared these sentiments, but Portland in general was a more tolerant city. Portland offered opportunities for work during timber and mining off seasons. The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in California also brought Chinese laborers into the Northwest as they followed the railroad north, and by 1869 Portland’s Chinese population was at 8,000.

The 1880s saw more Chinese immigrants coming into the City of Portland. This was due to

surrounding states forcing, or legislating, the Chinese out of their cities. Some left the United States, and others migrated into Portland.

In the 1880s new laws were created that hindered Chinese laborers. In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, a federal law that prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for ten years. While Chinese populations decreased in many cities due to this law, Portland instead saw an increase, likely due to the tolerance of the city.

Portland was unique in many ways, leading to diversity in the early Chinese community, and how they situated themselves within the city. The city of Portland had a reputation among Chinese immigrants of being a tolerant city. While some cities in Washington and California saw violent anti-Chinese labor protests around the time of the depression in 1892, no such protests ever occurred in Portland. The ways that the Chinese interacted with the population at large also set it apart from other cities, while they could not own property, in Portland they were free to occupy buildings throughout the city.

As the Chinese began to call Portland home, two areas sprang up: an urban area referred to as Old Town

vegetable gardens created by the Chinese that helped feed the people in Portland

Chinatown Neighborhood, and rural area known as the Chinese vegetable gardens. Both of these areas coexisted at the same time within the city. The Chinese vegetable gardens were located in the Tanner Creek Gulch area. They were first recorded in 1879 when improvements to the area were made, to make it suitable for living and farming. These gardens supplied vegetables to all segments of Portland’s population.

Here is some of the Japanese history, taken from a free I book written by Peter Pappas, mostly about how the Japanese were treated during WW2

Little Japanese Girl in Portland

By February of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 cleared the way for the forced removal and incarceration of Portland’s Nihonmachi.

Once the exclusion orders were issued, Portland’s Japanese Americans had only a few days to get their business affairs in order before having to report to the Portland Assembly Center. Many were barred by the Alien Land Laws, from owning property, thus their businesses investments were in fixtures and inventory. Limited to only a suitcase of personal possessions, many had to leave everything behind or liquidate possession or properties in quick sales for only pennies on the dollar. Within days Nihonmachi’s residents were stripped of their civil rights, freedom and financial equity.

Early Portland had both a Chinese and Japanese population

Their first stop was the Portland Assembly Center operated in the summer of 1942. It was one of the many temporary incarceration centers built in large population centers on the west coast until more permanent centers could be built further inland. The Portland Assembly Center was really the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Pavilion. Plywood construction and rough partitions could not cloak the smell of manure, or deter the swarms of black flies.

For four months, over 3,500 evacuees made do in this roughshod temporary housing with minimal plumbing and little privacy. No information was given on how long they would be at the assembly center or where they would go next. See interviews with people incarcerated at that center and contrast them with the cheerful photographs circulated to the US public. Most of Portland’s Nihonmachi was eventually moved from the Portland Assembly Center to more permanent incarceration at the Minidoka War Relocation Center.

But after the war … the Japanese town was not there… I don’t think there was that central feeling of Japantown. ~ Former resident

Released from incarceration in 1945, Portland’s Japanese community faced tough decisions about where to “restart” their lives. Most had lost their livelihoods, homes and possessions in the wartime roundup. Released from incarceration in 1945, Portland’s Japanese community faced tough decisions about where to “restart” their lives. Most had lost their livelihoods, homes and possessions in the wartime roundup. You can read more from Peters free book!